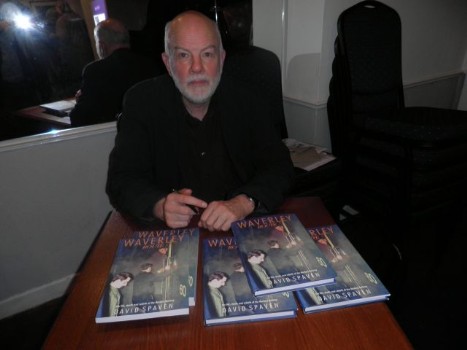

4th January 2014: the Borders Railway by David Spaven

David's childhood affection for the mainline railway through the Scottish Borders was cemented by camping holidays at Riccarton Junction which until 1963 lacked road access. However his purpose in writing the book Waverley Route published in August 2012 by Argyll was so that the reasons could be understood for its closure and forthcoming partial revival.

Enjoying romantic associations with Sir Walter Scott, the Waverley Route linking Edinburgh through the Scottish Borders with Carlisle was a prestigious railway but not the fastest, well regarded but tough to operate with its summits at Falahill in the Moorfoot Hills and Whitrope in the Cheviots. Even a hundred years ago the Midland Railway had to pay the North British Railway to operate its through expresses from London St Pancras, and in the bad winter of 1963 the Route was closed by snow for 18 days, then operated as a single line for a further 25.

The Beeching Report of 1963 on the Reshaping of British Railways recommended for closure four Scottish stations in the top revenue-earning category. Those at Stranraer and Thurso were quickly reprieved, but for Galashiels and Hawick on the Waverley Route there was to be no such outcome. Many of its other stops had a poor service, with for example Gorebridge boasting latterly just one train a day on Mondays-Fridays into Edinburgh, while there

were far too many surviving stations with several such as Steele Road serving just a handful of farms - and no investment had taken place in facilities like observation cars to boost the Route's tourist potential.

With the closure of its last branches like Kelso in 1964, it was hoped that the main line might survive at least as far as Hawick, but this proved to be not so when a closure proposal was published for the entire Route. Receipt of only 508 objections undermined the case for retention, but the Transport Users' Consultative Committee for Scotland duly reported that closure would give rise to significant hardship. There followed nineteen months of limbo as the focus shifted to London, where ranged against pro-closure transport minister Barbara Castle who saw the Route as a duplicate line was redoubtable Scottish secretary Willie Ross who on many other fronts successfully fought his country's corner. Then in April 1968 Castle whose record in other respects had been more commendable was replaced by Richard Marsh who confessed to having had not the slightest interest in transport, and the Central Borders Plan published on the 19th of that month proved completely lukewarm, since despite recommending a new settlement at Tweedbank adjacent to the Waverley Route none of its 21 recommendations supported the railway and not one of its 577 paragraphs was devoted exclusively to the railway issue.

Absent from a ministerial committee which met on 21 May 1968 were Board of Trade ministers Tony Crosland and Lord Brown of Machrihanish who might have supported the Route's significance for regional development. When the committee decided that the Route in its entirety must close, Ross referred to the Prime Minister a threat by young Liberal MP David Steel to resign and force a by-election, but Harold Wilson replied that he did not think it

right to reopen the debate. Only then was a campaign mobilised, and Hawick housewife Madge Elliot collected 11678 signatures to a petition which she delivered in December 1968 to Downing Street with Steel and Edinburgh North MP Lord Dalkeith, heir to the Duke of Buccleuch. Newcastleton minister Rev Brydon Maben was escorted off the premises for trying to deliver a separate Liddesdale petition on the railway to the Queen at Balmoral, and when the final train conveying Steel to London reached Newcastleton the level crossing gates had been closed against it by villagers led by Maben who now stood defiantly on the track. Police reinforcements sent for bizarrely included the minister's son, but Steel persuaded the crowd to disperse on condition that Maben would not be prosecuted and the train went on its way 117 minutes late.

Despite an abortive attempt to resurrect the Route as a tourist attraction, track-lifting was completed in 1972 and there followed twenty wilderness years during which the residual road parcels service ceased and development was allowed to encroach on the trackbed, including in the 1980s a row of houses at Gorebridge. The Cockburn Association's call at the public inquiry into the A720 Edinburgh City Bypass for provision of an underpass for the Route

was to no avail, and further encroachments included a bungalow at Stow and the Eskbank bypass, which created a roundabout where there had been an embankment at Hardengreen. It is reckoned that these erosions of its formation have added 40% to the cost of reinstatement, but the tide began to turn when local architect Simon Longland conducted a survey on his motorcycle which showed that the great majority was intact, leading to the creation of Borders Transport Futures to argue for revival of a passenger

line at the north end and a freight line in the south until the latter became ensnared by the falling price of timber.

On moving into the area as an environmental adviser to Borders Council, German expatriate Petra Biberbach found herself astonished that it had no railway, so helped found the Campaign for Borders Rail under whose aegis Madge Elliot collected 17200 signatures on a petition to the Scottish Parliament. Now reopening was seen as a tool for economic recovery in the face of job losses at Borders electronic plants and the remaining textile mills. A £400k study recommended a passenger service terminating at Tweedbank, initially without a station at Stow until a local campaign featuring a straw locomotive secured its inclusion. Then in 2012 a deal was struck between the Scottish Government and Network Rail for the Route to reopen between Newcraighall and Tweedbank in 2015 with seven stations including a public transport interchange at Galashiels.

Trains will run half-hourly throughout the day, taking 55-59 minutes to link Edinburgh with Tweedbank. The Campaign remains active to promote the best possible service because with the lengths of double track reduced to just 9 out of the 30.4 miles there is a feeling that reconstruction of the Route is being skimped in a way that would be unacceptable for the new roads being built over the railway (and paid for by the railway scheme).